A Disturbing Trend Among Boomers

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), drinking among seniors age 50 and older is on the rise. In fact, seniors make up the segment of the population for whom drinking has been increasing most. In one survey of seniors, 15 percent of senior men and 12 percent of senior women stated that they drank more than the limit recommended by the NIAAA on a daily basis. In doing so they put their health at risk. Why? Because as we age our bodies metabolize alcohol more slowly, meaning that alcohol (a toxic agent) remains in our bodies longer. There, it can exacerbate medical conditions such as hypertension, memory loss, diabetes, and neurological problems, all of which are more common among older adults. And drinking in excess of even a single glass of wine a day can increase the risk of cancer.

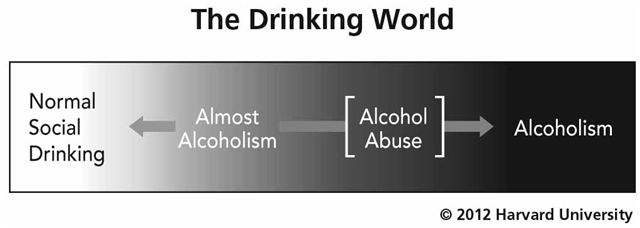

It would be wrong to characterize the above group of seniors as alcoholics. Only a small fraction of them would meet the criteria used to make such a diagnosis. That said, a large percentage of this group have also gone beyond what could be called “normal social drinking,” meaning a cocktail, a beer, or a glass of wine once or twice a week in the company of friends. On the contrary, a great many of these seniors drink every day. And they drink alone. They are not alcoholics, but as the following diagram suggests, many of them may very well be “almost alcoholics.”

What Is An “Almost” Alcoholic?

Almost alcoholics fall in the “gray zone” that occupies the fairly large space that separates normal social drinking from drinking that would qualify for a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence (alcoholism). Some people’s drinking will place them fairly deeply into the almost alcoholic zone, whereas others may have only recently ventured there. That space is depicted in the following diagram:

Almost alcoholic drinking, especially among seniors, is most often defined by the following circumstances:

- Looking forward to drinking.

- Drinking alone.

- Drinking to relieve stress (due to chronic illness, financial difficulties, etc.)

- Drinking to relieve boredom or loneliness.

- Drinking to relieve physical symptoms (pain, insomnia).

The above was certainly true for Laura, whose husband Brad had died two years earlier following a four-year battle with colon cancer. Married 52 years, they’d raised two sons, both of whom had families of their own, and both of whom lived many hours and many miles away.

Despite being invited by both sons to do so, Laura decided against selling the house and moving. She had a circle of friends, she told her sons, and in addition she did not relish the idea of cleaning out her possessions, leaving the house she and Brad had occupied for most of their married lives, and assimilating to a new community.

So Laura stayed in the house, in the company of a cat she decided to adopt from a woman in her church. She found “Henry” to be a good companion. She also made a point of going to church every week, and continued with a book club she’d been part of for many years. Despite all of these things, Laura admitted she often felt lonely. Moreover, although her own health was holding up well, some of her closest friends were less fortunate. The net result was that her social life was slowly but steadily dwindling.

As her social life dwindled, Laura’s drinking increased. Whereas she once drank strictly at social occasions, she now found that a brandy or two at night helped. To quote her, “It settles my nerves.”

What Laura was doing, of course, was compensating for her loneliness by drinking. The amount of brandy she drank slowly crept up on her, until two events happened. First, her oldest son asked, during their weekly phone call, if Laura had been drinking. He politely but firmly pointed out that she was slurring her words. Embarrassed, Laura replied that she’d had a brandy that day, as the weather was cold and she felt a chill. In truth, she’d downed four brandies over the course of that Sunday afternoon.

About a month later Laura walked down her driveway to fetch the newspaper. On the way back she tripped and fell, bruising her leg. The pain was bad enough that she decided to drive to the local emergency room. While she was there, awaiting the results the house of a CT scan, the doctor asked her how much she’d been drinking that afternoon. Again, Laura was embarrassed, this time even more so because the doctor told her he was concerned enough that he would not allow her to drive herself home. Humiliated, Laura was forced to call a church friend, who came and drove her home.

A Familiar Pattern

Laura’s case is hardly unusual. On the contrary, among her peers she has lots of company — perhaps millions — who are turning increasingly to alcohol as a way of compensating for loneliness, boredom, or stress. They may not be alcoholics, but they are “almost” alcoholics. Most importantly, their physical and/or emotional health is suffering as a consequence of their drinking, but they do not see that connection. In future blogs I will describe a couple of solutions that seniors who find themselves in this situation can turn to as a way of moving back out of the “almost alcoholic” zone.